THE MARCH OF HOPE

THE MARCH OF HOPE

Interview with Jim Kroft

Who is Jim Kroft? I am someone incredibly grateful for the opportunity of being alive.

“The March Of Hope” is an independent road movie, starting off with two friends (yourself alongside your friend and co-producer Bastian Fischer) setting out from Berlin in the hope of learning first hand about the lives of refugees in Europe, all from the perspective of a yellow van: (a)What prompted you to make a road movie about Human Rights? (b) Tell us a bit about the ways that this great yellow van participated...

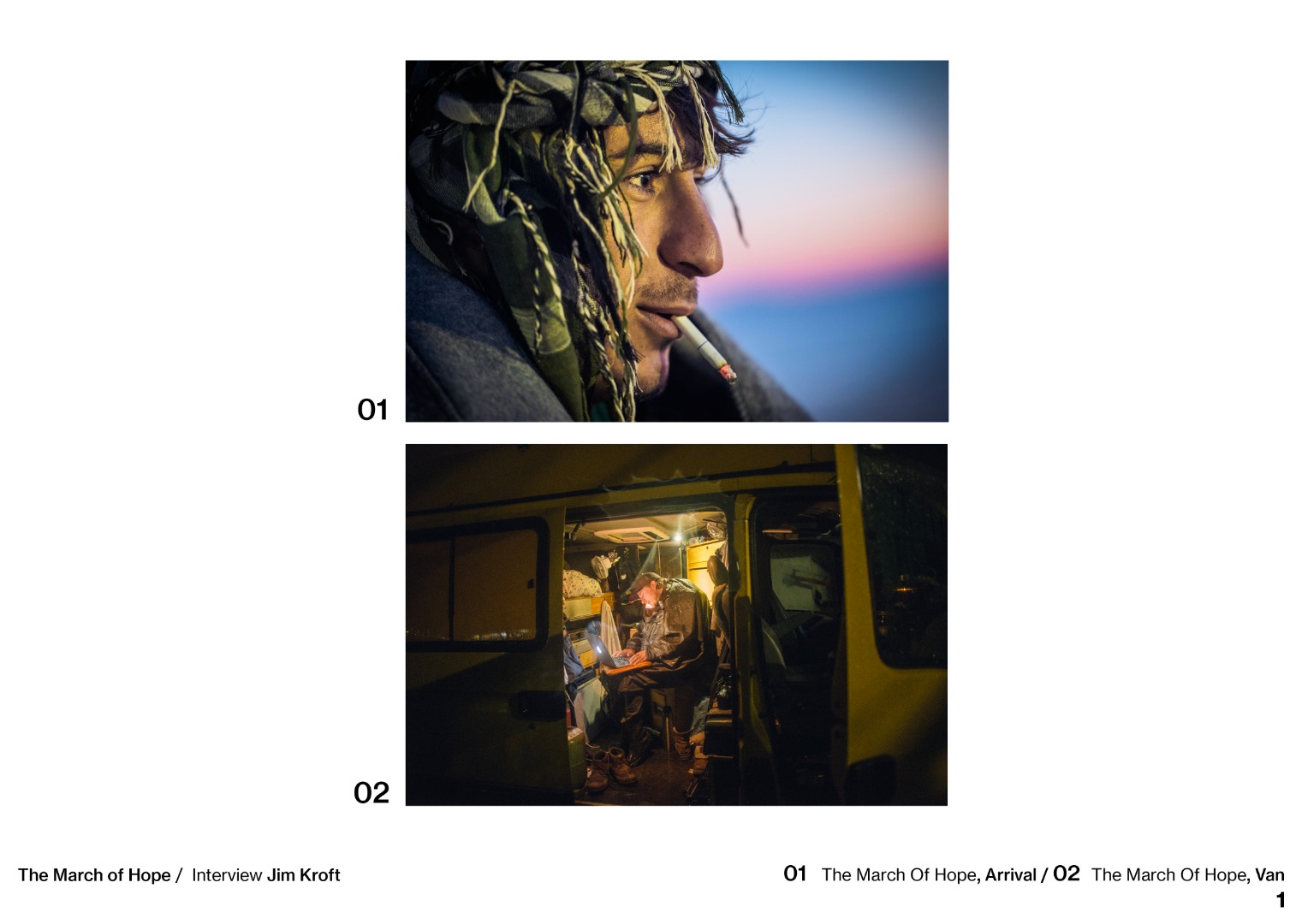

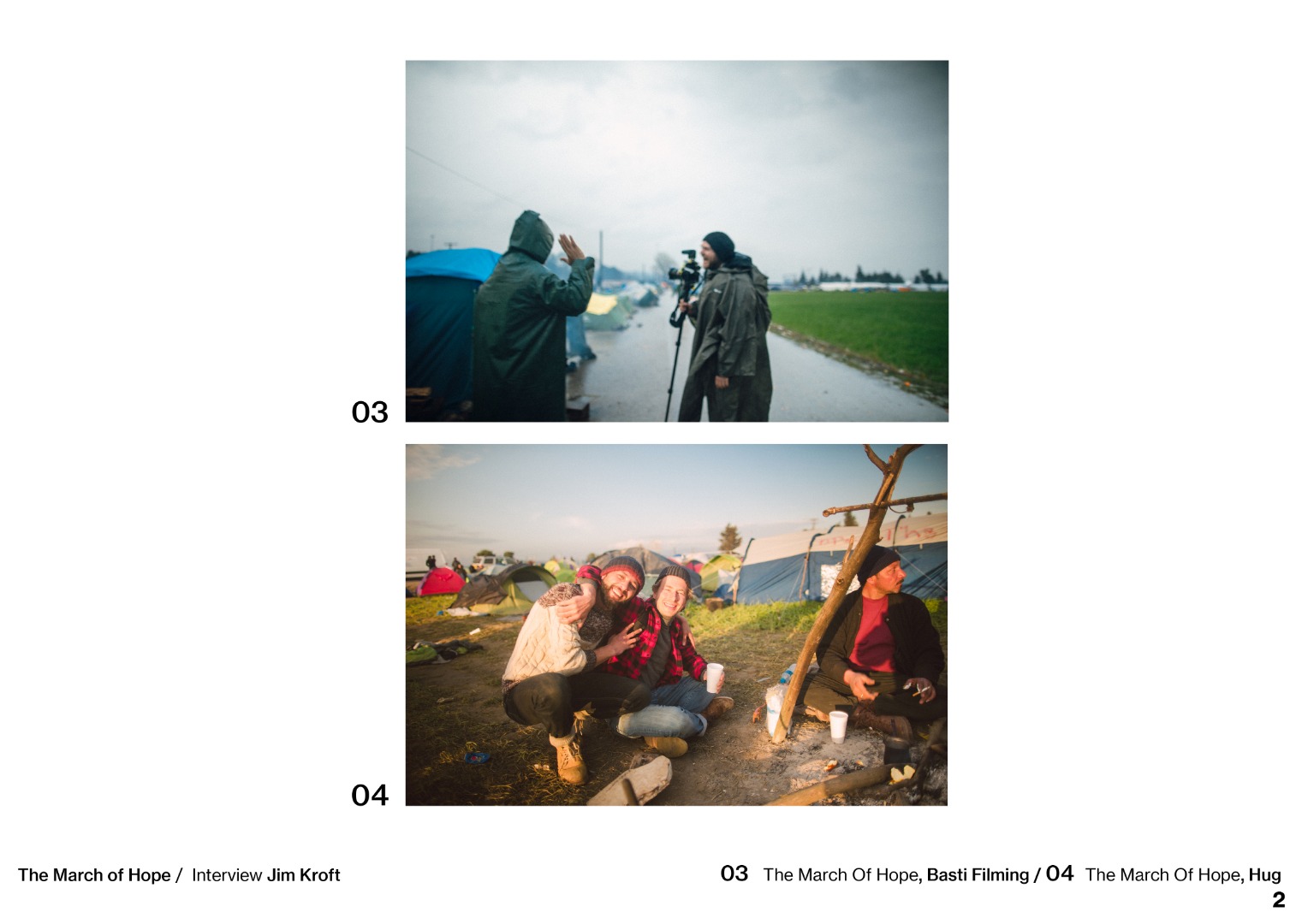

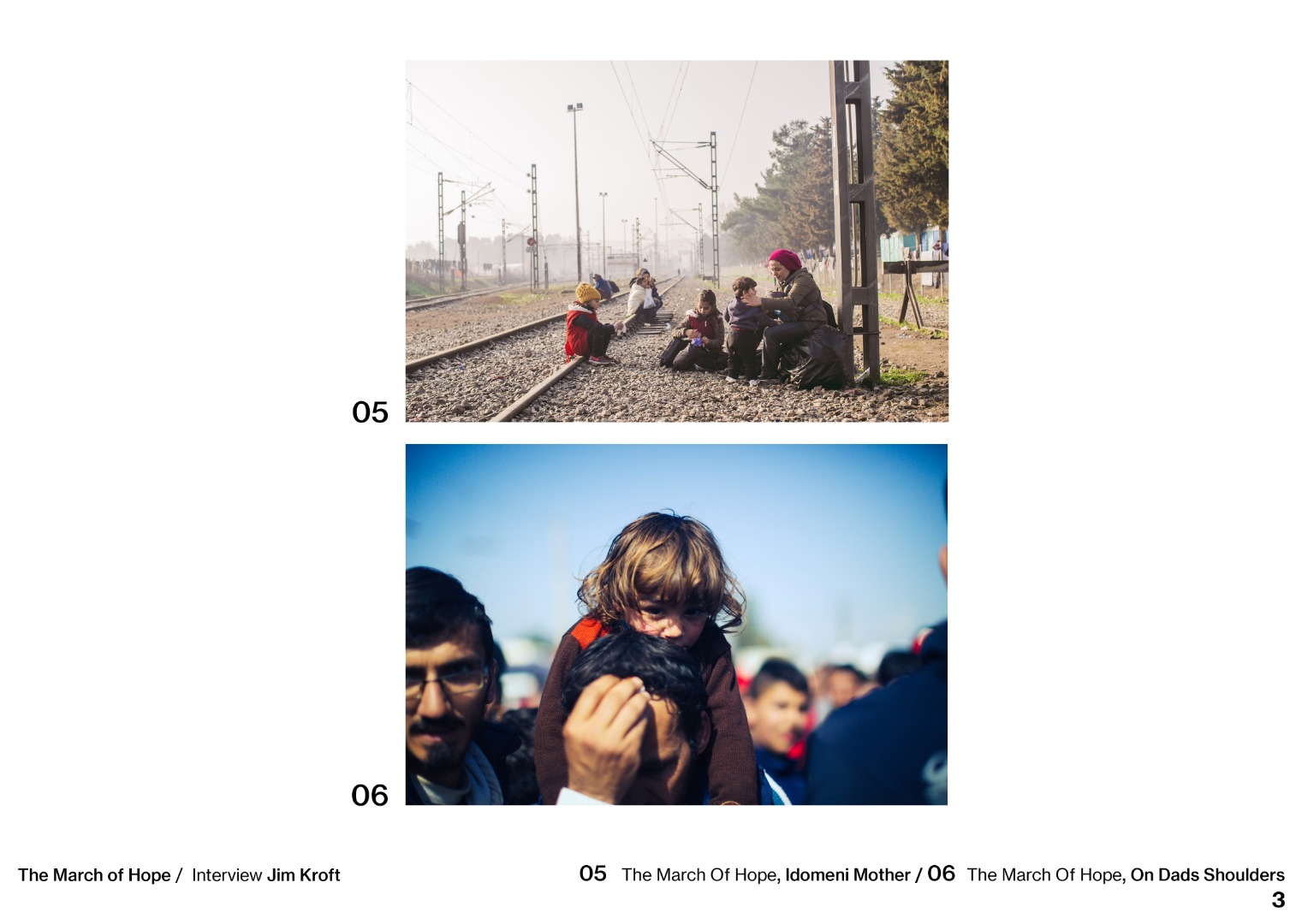

I have been working on a project called “Journeys” for the last years, of which “The March of Hope” is the fourth instalment of a broader series. During each Journey (so far through China, East Africa, Russia, Europe and the US) I have looked back at my own continent and it has struck me how, each time I have returned, it has been changing. Nothing has concerned me more than both the tone of the conversation and the erosion of Human Rights. I realised during the journey which preceded it - 15000km through the Russian winter - that I wanted to come home and try to find some way to make a stand for Human Rights. Less than a month after coming back, Basti drove round to my house in his yellow van, and we were on our way to Greece. Little did we know that it was the very non-existence of a budget which would be the very most important factor of our filming. It was the mobility of the van, and the fact that we could stay in the heart of things that enabled the opportunity for a different insight into what was happening.

What does the film’s name allude to, both literally and symbolically?

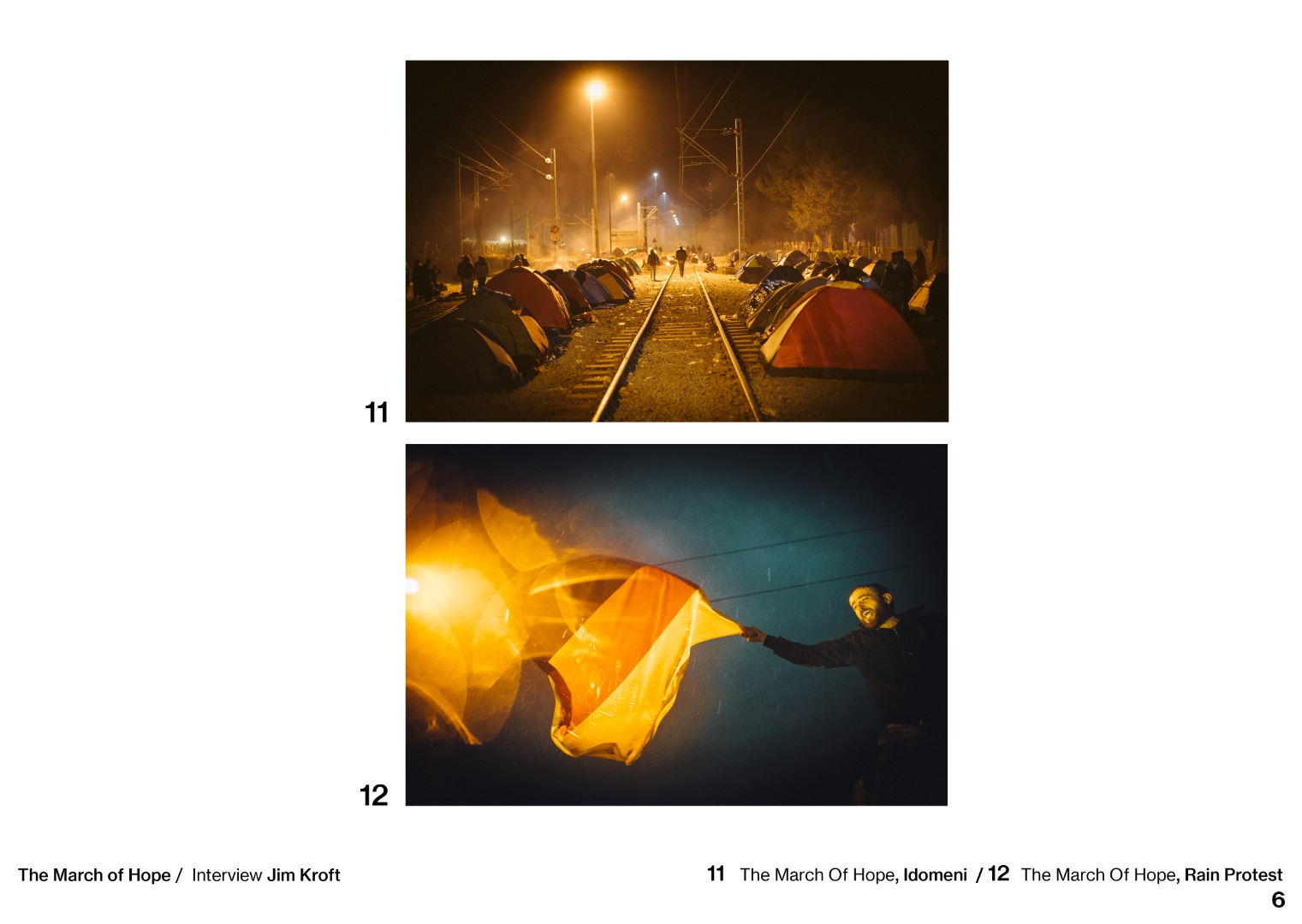

The name “The March of Hope” derives from one of the key instances in the film, when several thousand refugees, stuck in the mud in Idomeni after the Balkan route shut down, decided en masse, to head on foot to Macedonia. It was called “The March of Hope” - that is the self-determined effort to reach asylum - no matter what the cost. Even though that particular effort failed - the name stuck with me. I know many people are downcast about the state of things currently. However, in the greater scheme of human history “Human Rights” are relatively young - the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was only signed in 1948. It is something I believe is an apex’s of human civilization. Yet like any long struggle - it will hit its dead-ends, have its detractors, and face its challenges. It is simply our challenge as human beings to make our own stance for the values of our civilization. And part of that challenge is to stand up when core rights are being eroded. I personally think that this sense of helplessness before things is a kind of indulgence. We have to be willing to focus on what we ourselves can do within the limitations of our own lives. And trust in the significance of small acts.“The March of Hope”, is simply about having the courage to continue the struggle...

What is the most important take-home message for the viewer?

My hope with the movie is to personalize what human beings go through. People talk continuously of the “Refugee Crisis” as if it is something inanimate, a statistic. Although I appreciate the logistical challenges of migration as a phenomenon, I think there is a huge danger in looking at it “top down.” It is the statistics and numbers which objectivize something which is actually experienced by human beings themselves. With the film, I have tried to stay true to the bond of friendship which was formed with some of the people I met. I say, people, rather than refugees because I look at the film not as a film about refugees, but as a film about humanity - about people.

One of the multiple aspects explored in the film is how a human right is something universal and for all humanity...

The idea of the Human Right impressed itself upon me during the journey, not as a concept, but as something living. What are the basics of being a human? What do we need? What happens when these things are taken away from us? And the more I witnessed the realities on the ground, the more I came back to “The Universal Declaration of Human Rights” - and recognized the power of its prescriptions. When a child is born, it has a birthright to receive food & nourishment. A teenager has the right to live with shelter and in safety. And a parent has the right to seek asylum when madmen are bombing their homes. It seems obvious really. But to understand it, sometimes you have to witness these things yourself.

In “The March Of Hope,” rather than being a film on refugees, it is a living document to the power of the human spirit, giving voice to the ones whose voice is ironically and unfortunately hard to be heard and whose spirit is hard to be conceived by our so often impenetrable Ego walls. What are the “ingredients” composing the human spirit under these challenging conditions?

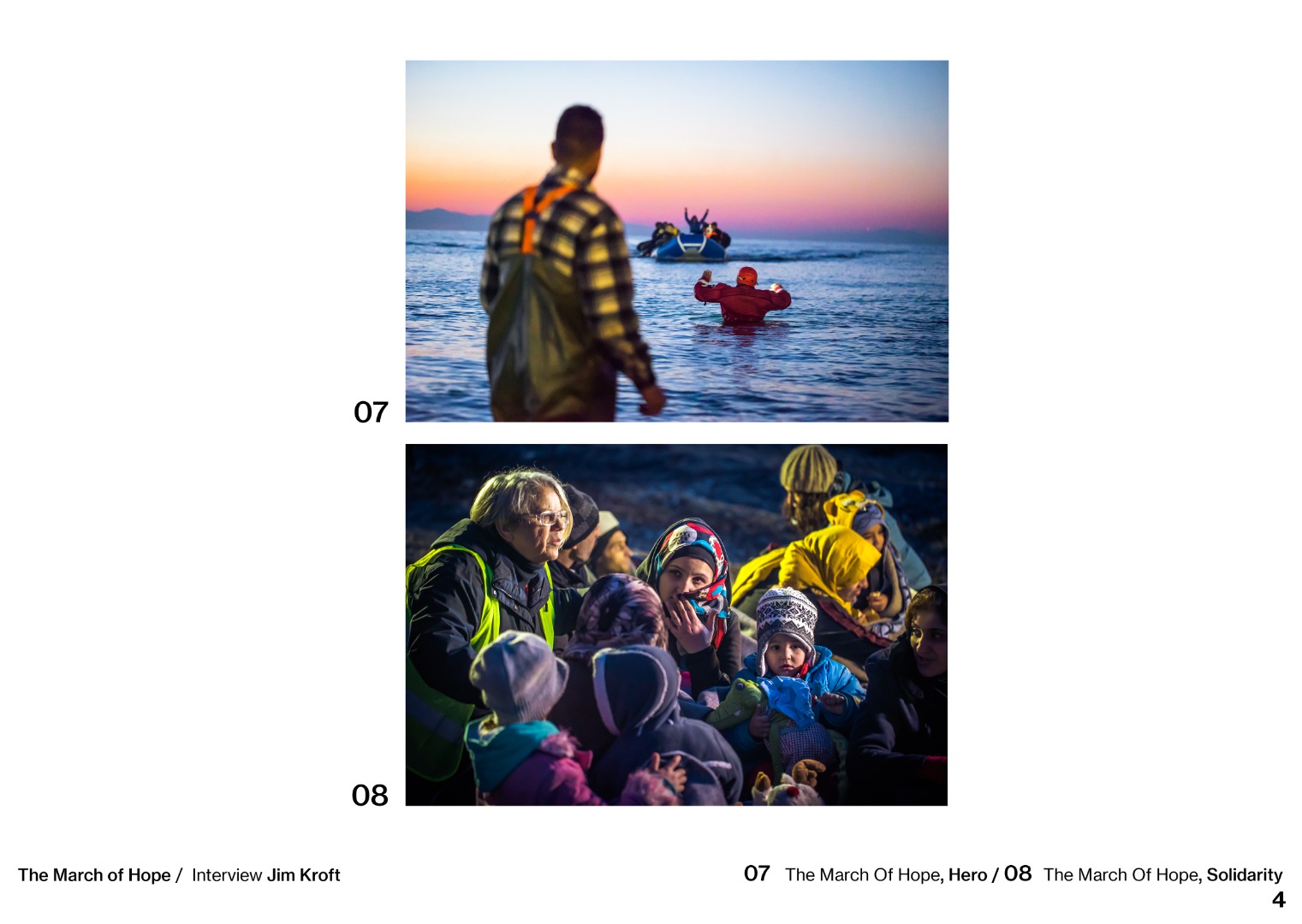

What amazed me during my journey was the courage I witnessed under the most awful circumstances. I have never witnessed something like the dignity with which people kept normal life together while stuck in the endless rain and mud of Idomeni. Human beings keep themselves going by doing the basics as best they can; looking after the kids, sharing food, little acts of kindness, passing on information, laughing when there is just bloody well nothing to laugh about. In being invited into these moments, I simply marveled at them.

What’s your opinion on the press/media handling of the migration issues?

I met some incredible journalists along my journey, and am lucky to call several reporters great friends too. I marvel at the job they do - every day to be on point, to look for the truest account possible, to challenge oneself, to so often be away from home. The press is under heavy fire at the moment, and I think we all need to speak up far more because many reporters are in danger, being incarcerated, and even killed, worldwide. It’s a symptom of the “strong-man” narrative in politics. Human beings so often flock to tough-guy leaders when the world is particularly on edge when there is great uncertainty. And those that choose to challenge those leaders - often journalists - often come under fire, and I think that is happening at the moment. Regarding the refugee crisis, how can I faithfully make such a broad critique? In the press, there is often a fairly clear divide often between the “security perspective” and the “humanitarian perspective.” And while each has its legitimate points, I don’t see why they have to be mutually exclusive. What upset me during my journey was simply that I felt that there was a relative dearth of reporting. In the press, there was what one journalist called “refugee fatigue.” And yet daily I saw a humanitarian crisis unfolding on European soil. And beyond that, terrible human rights abuses on the borders, which (at the time) I couldn’t see reported in the news. And yes, being on the ground it was frustrating to see the disconnect. Even at this moment in time, there are thousands of refugees incarcerated in detention centers in Greece, living in abominable circumstances and completely shaming to us as Europeans. And again, I feel it is terribly underreported. So yes, I can critique the press in certain limited ways - which is healthy to do - but at the same time, I stand in solidarity with journalists. We need to stay vocal in that support because the press - and the journalists - are under attack.

The Boat For Sarah Project: Tell us about your meeting with Sarah, and in what way it impacted you, to the point of being the reason behind your successful thirty thousand crowdfunding campaign?

There is a point in your life when you realize that there is only one thing to be done. That moment to me happened on a beach on the coast of Lesvos. A particularly terrible boat came in. Awful, unimaginable. It had been stuck out at sea, the people came in, freezing, drenched, to a man, woman, and child, hypothermic. It was my first night on Lesvos. Despite having read so much, I was just so woefully underprepared. You can’t bloody well conceive it. And I was filming, the camera being kind of a safeguard to the terrible reality perhaps. And at one point a little girl came off, drenched, shivering, at death’s door. And there was just no one there, all the aid workers were already stretched beyond human capacity, and by that I mean, giving CPR on the beach to children, warm clothes to adults, struggling to get disabled elders off the boat. And it was then I saw a little girl, all alone amongst the madness, and it was just terrible. I did what anyone would do. I picked her up to take her in, and then she lost consciousness, head rolled back in my arms. I was panicking and screaming “doctor, doctor.” Just terrified she was losing her life in my arms and cursing God that of all the people she could be met with, it was a useless artist, probably as terrified as anyone. The rest I reflect on it in the film. But it was the moment I ceased to be an observer of the refugee crisis and became a participant. And it is that which motivated the fundraiser. Simply to challenge the limitations of my own power to help. To stop wondering “what could I do” and to get on with the business finding what I really can do. And “The March of Hope” is an extension of that effort. To offer other people a type of participation through a very personal experience of a very objectivised subject.

What was like being present during the apotheosis of the “Refugee Crisis” as the EU-Turkey Pact was agreed and the “Balkan Route” was closed?

I look back, and it is quite extraordinary that we happened to be filming during these two absolutely critical moments politically. It provides the context, background, and ark of the story we witnessed, participated in, and filmed. It gave us the opportunity to make a very different account of these two events - by showing the effect they had on people on the ground. Unfortunately, the reality is that they were executed with profound incompetence, and the effects on the ground were devastating. That was not just in terms of the effects on the refugees themselves, but also regarding the lack of information, help, support and money for the aid workers - both governmental and non-governmental. As someone who supports the EU, I was shocked at how incompetently the show situation happened. And now, that has turned to outrage in witnessing the continual attacks and incarcerations on aid workers, humanitarians, and activists - especially on the Greek Islands and in Italy. The EU needs to come out in support of these people, rather than allowing them to be attacked. It is an outrage that our politicians are complicit in the assault on humanitarians.

Kids, children, blind men, parents, disabled people, old people, and so on, all under inconceivable living conditions, fearing for their lives, and not knowing what fate awaits them; nevertheless, you managed to bond with them. Could you share how these people entered your heart, and how those friendships managed to solidify under such a paradoxical context?

One day, during our stay in Idomeni, a Syrian man came up to me. Our van had been parked day and night next to a particular group of refugees. This man had gleaming eyes and a wicked smile. He knocked on the door of the yellow van. I rolled down the window. What did he want? To give me a bowl of delicious food. He joked that he had seen Basti and I eating cans of tuna in the back of the van and said he took pity on us, and chuckled devilishly. Over the next weeks, Muhammad, and his group became our friends. They invited us to be a part of their “Giran” - neighborhood. And we’d talk about what was going on, and Muhammad would quote Victor Hugo or Voltaire, or just tease at how bad our geography was. One day he told us, with glinting eyes that our yellow van was the “penthouse” of Idomeni! And he was quite right. And I told him that the worst thing about being in Idomeni was that I myself was not allowed to grumble or complain! Even if it was cold and wet in the van, at least it was proper shelter and not a summer tent in the rain. Who knows why, and how friendship forms. But what I do know is that it comes out of sharing something. And for that time, we shared a point of our lives, and whenever we chat now online, Muhammad and I always talk of the Giran - it lives in his heart as much as mine. He is now safe and reunited with his son. With his degrees in law and medicine, I am sure he will have more subjects to tease me about when we meet again next!

Would you consider those volunteers/aid workers as today’s exemplars of real-life heroes?

Oh absolutely! One of the great joys of my journey was to witness the work of the volunteers, who had heard the call, and answered it, from all over the world. It was really something extraordinary to see how people of every type of age, background, and nationality responded - I think the oldest person was a Swiss lady in her 70’s! It was also very moving to see the bonds which formed between people too. The world is so focused on what divides us that it tends to forget that our humanity forever connects us.

In the movie you successfully document the lives of refugees in Europe, through a humanistic, creature to creature, being to being standpoint. Who were your teachers during this trip, and what are some lessons learned?

I could never have known how much this journey would teach me. Those lessons yes had political dimensions and a deepening sense of what people had fled from. But nothing educated me like the sheer courage I witnessed. Every single day in Idomeni, a historic hell hole, there would be wonderful moments of laughter. It would emerge in ways you would never expect, little Karaoke impersonations, or sharing the comedic value of a misunderstanding, such as the refugees always, and continuously, believing our yellow van was the DHL van. There is no educator like witnessing genuine courage, and perhaps nothing more inspiring to the soul. I set out trying to contribute, but it was I who received, in that, the greatest gift.

In your opinion what gets in our way, and almost hijacks our view of the situation and the persons involved?

The first impediment is that the “refugee crisis” is seen in terms of numbers and statistics - as a phenomenon. You cannot understand anything about it unless you have felt it in some way. What these people actually go through. For that matter - when we say “crisis” - it is not a crisis of Europe - it is a crisis for the refugees. The second impediment is simply that the reality is that most people have never met a refugee. Their perspective on the situation is purely derived from the newspapers. Without any human contact, it is so very easy to “objectivize” and treat/consider others as alien, other or worse.

What role the arts could play in the face of this humanitarian crisis? How could culture be relevant to people who have lost everything and how did you experience this “symbiosis”?

One of the magical realizations of the trip was to see and witness how culture travels in the human spirit. But not just in the spirit, but in the choice - in leaving everything behind, to carry paintings, musical instruments, art materials. In the West, of course, art is essential to us. But when you see someone leave his home with nothing but his Tambura - such as in the case of Recit Bider - then you see that art is not just a choice, but an exigency. Another person I met, smuggled her paintings out with fear of death if caught by ISIS. I can’t imagine that courage. But even more so, if you think about it, what it teaches us about what art means to the human soul. In this, it is not just reflective of the soul but is it. Within the choice is the decision “I would rather die than live the lie of sacrificing the things that make me.” I will never find a more genuine sense of what art is, of what it means, and its incomprehensible power.

When you close your eyes and recall of your time in Lesvos and Idomeni, what comes to mind?

Something Basti said on departure was “I never felt so close to life as during our time Idomeni” - and that I still understand and feel. So it is a paradox really for me to look back. Because it was shocking to witness such conditions on European soil. It was devastating to see suffering, sometimes terribly so. And hand in hand came their opposites. The brother of suffering being kindness, and the sister of struggle being laughter. I can’t look back on time one-dimensionally. And the paradox deepens when I speak with some of the refugees with whom friendships have developed further since then. Even they look back, and remember something somehow positive emerging out of the sorrow, struggle and despair of that time. However, I must point out, that is remembered by people who eventually got through the border to safety. I expect that memory is very very different for those - those many thousands - who are still living in camps in Greece and hidden away shamefully from European memory and conscience.

Do you tend to question yourself on a personal level?

Yes of course. I think doubt and uncertainty are often valuable precursors before you take any definitive action with your life. I find that often a project is preceded by a period of stuck-ness and the older I get, the more I understand and value these periods. They are a part of the process itself. I find it healthy not to reject them, but to accept them and to “sit” within them. There are also other times when you just feel something in your stomach, and you know you have to act. With “The March of Hope” there were many questions beforehand, but then the will to act happened very quickly and very clearly.

Where do you see beauty?

I see beauty in the capacity to participate. And freedom in living in a society where we can freely do so. Standing for Human Rights is not just about protecting the vulnerable. It is about recognizing that the first thing any despot or dictator does, is banished individual rights. It is then that the beauty of freedom and participation are dismantled. For me, Human Rights also guard the aesthetics of our culture, as well as its moral backbone.

What’s up next for Jim Kroft, the artist, and what’s up next for Jim Kroft, the humanitarian artist?

I will release my new album next year “Love in the Face of Fear” - but it is a more a message, and in that, a type of humanitarian project. How do we respond to the fear and brutality? By always returning to that which is most enduring & most indestructible; love.

Interview / Content Editor: Annie Markitanis

.jpg)

.gif)